3.

Challenges Inherent to Bonsai Art

Lessons from landscape painting

Landscape painters are set with many of the same kinds of challenges that we bonsai artists face. After all, what they create are not actual landscapes, but rather strokes of paint on a canvas. This presents the artist with a difficult task of communicating the impact of what is familiar to people without using any of the natural elements present in the environment he/she attempts to depict on canvas. Furthermore, the artist has to make the scene seem important or meaningful to the viewer. Doing this requires the use of some useful conventions of artistry.

A couple of the most important facts that the artist has to come to grips with are:

- The artist can communicate very little with a verbatim copy. Merely painting a picture of a scene from nature exactly as it appears in nature will likely result in a dead work. The painting will have little impact because there is no composition, emphasis, interpretation, emotion, …no human element. Artists describe and provide a point of view — they do not merely record.

- Landscape painting (and every other art) is largely concerned with human things. Every part of a painting or sculpture or musical composition or bonsai is often without life unless it embodies or references humanistic elements — human experience, human emotion, human qualities, etc… If you learn nothing else in your study of artistry, learn this.

There is no reason to paint a picture or compose a piece of music or snap a photograph if it is not an interpretation of what the artist feels or what he wants others to feel or share in.

The artist tells a story. The story that an artist tells must communicate human things to the viewer or listener. In most cases, a painting of a stream in a valley is only created because the artist wanted to communicate something about what he saw in a valley by a stream or what he felt when looking at that scene. The valley and the stream are just natural references to our world, but the message — the point of the painting — is what the artist will emphasize by way of artistic conventions.

These artistic conventions are the techniques the artist uses to manipulate the elements in the scene to emphasize the things he wants the viewer to understand as important. So the reality of nature is merely a reference point from which the artist creates an emotional experience or a meaningful story. That story or the eventual compositional elements of the painting are not at all about trees and streams and hills and clouds.

These facts are not the entire measure of art, but they constitute a great proportion of what we artists need to have in mind (or just simply do naturally) when we are creating art.

Now, back to Bonsai

So it is the same for the bonsai artist and his medium: the tree, pot, and companion elements. The results of successful bonsai design are not so much about the trunk and the branches and the leaves, but about the story and emotion that the artist wants to communicate; the human things that can be communicated.

Portraying a meaningful image of nature with bonsai is not as easy as it might seem. The fact that bonsai are not full sized trees out in meadows or on mountainsides, but rather very small trees growing in pots, brings with it many artistic challenges; not unlike the painter who uses strokes of paint on a canvas instead of real people or real trees or real mountains. Or the composer who uses notes and sounds from various instruments instead of speech or video.

In order to compensate for these great differences in size, perspective, environment and age, bonsai artists have to employ certain clever and communicative, even deceptive, techniques. These techniques are artistic affectations used to portray the image and feeling the artist wants the viewer to see and feel. These affectations of form and composition can be considered the syntax of the language of art.

Communicating Visual Characteristics

Size

Size is the most obvious difference between bonsai and regular trees. Bonsai will usually be 90 cm tall, or less. Often we work to portray an image of a very large tree and this presents challenges we must address in order to be successful at presenting a credible image. Here are a few ways of addressing this challenge.

Lean the tree forward slightly

Manipulating the trunk line so that the bonsai, the crown especially, leans toward the viewer is effective for offering the perspective that the tree is towering over them. Usually when we look at trees, we see them from our perspective of standing on the ground under them or from nearby. This common vantage point presents an image we learn to expect when looking at trees. By leaning a bonsai toward the viewer, he gets something of this same perspective, which helps the bonsai to convey an image of great size.

Branch proportion

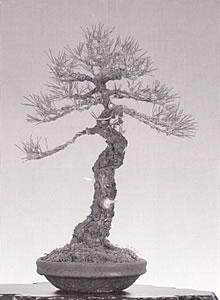

This needle juniper (above) is evocative of a very tall tree because of its trunk width-to-height ratio, the small branches (compared to the trunk) and the decreasing internodes from base to apex. Image courtesy of Bonsai Today.

One characteristic of small, young trees is that they generally have branches that are quite large in proportion to their trunk girth and height. Very large old trees (depending on the species) generally have branches that are quite small in proportion to their trunk girth and height.

With our bonsai, we can enhance the impression of great size by decreasing the branch sizes relative to the trunk size.

Note that the same is true for the canopy width. The shorter the branches, the taller the tree will seem.

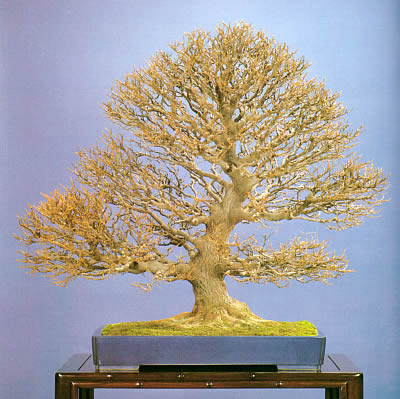

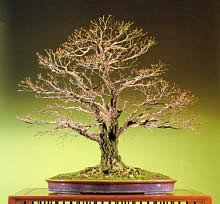

Photos courtesy of Bonsai Today.

Decreasing internodes ascending the trunk

From our usual vantage point on the ground, when we look up into trees, the branches seem to get closer together from base to apex. While this is generally a common trait in trees, our perspective exaggerates this impression, making the topmost branches seem quite close together. It appears to us that the trunk has greatly decreasing internodal spaces the higher our eye travels.

With our bonsai, we can slightly exaggerate this feature to further enhance the impression of great size or height.

Perspective

Because our common view of trees (when we really look at them) is from nearby and from the ground, the largest part of the trunk, the base, is generally quite close to us. The upper portions of the tree are more distant and above us. This distance and almost ground-level perspective lends a distinct form to the trunk taper. The trunk seems to taper quickly and our perspective also exaggerates the trunk size, relative to the height.

Somewhat exaggerated trunk size and taper

We can work to approximate this same perspective for viewers of our bonsai by making the trunk width and taper somewhat exaggerated. This is where the oft-cited principle involving the ratio of trunk width to height becomes useful.

Here below is an example of the affect of proximity on the trunk width-to-height ratio.

Here (above) we see a Sycamore tree as it appears from a distance. From this perspective, we see something close to the actual proportion of the tree. Notice that the ratio of trunk width to height is 1:19. In bonsai art, it is unlikely that anything other than a bunjin (literati) style tree will ever be successful using that ratio. For bonsai, a ratio of 1:3 to 1:12 is most often employed because it usually looks best (but not always). This is because we are trying to portray the image of a great tree and this ratio range more closely approximates what we see from our usual perspective when walking through our neighborhood or park or out in the wilderness.

Here (above) as seen from much closer, the ration is about 1:10 (almost half the previous ratio). We see how the same tree appears to have a more powerful trunk and more severe taper when viewed from close proximity. This feeling is something like what we work to convey with most of our styling and composition efforts with bonsai.

In the sketches above, notice how they could easily be the same tree as seen from varying distances. Left to right, they suggest: far, nearer, close-up. Consider these forms when you are creating your own bonsai designs.

Be careful not to try and follow any set trunk width-to-height ratio for all bonsai. The trunk width-to-height ratio is wholly dependent on the image you want to portray and not on any set formula. Width-to-height ratio is just one tool used for expression. If you use the same ratio for all of your bonsai, you effectively render null the meaningful expression that can be obtained by artistically using this tool.

Lower ratios are for conveying close proximity, power, age or strength. High ratios are for conveying a distant view, grace or certain environmental conditions or for portraying the bunjin (literati) style. Learn to use the ratio that is appropriate for each specific bonsai composition. Make this ratio reinforce the message you want to convey and let the other compositional elements of the tree and display support this ratio (more on this in thedesign integrity section).

Age

Usually, we develop and style our bonsai to convey a sense of great age. As mentioned before, bonsai often portray archetypical ideals. Regardless of the special individual character we work to portray with a bonsai, the impression of great age is almost always part of the message. However, most of the trees we most often work with are relatively young. Given many years of development, the telltale signs of age will come, but we also want our younger bonsai to appear to be very old. So, we must use artistic techniques to convey age.

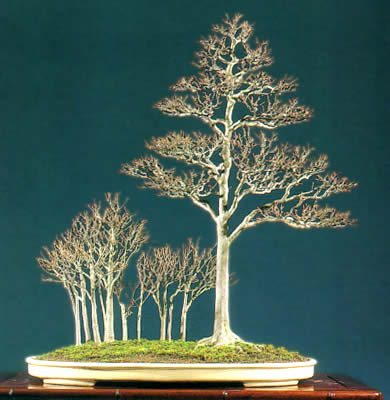

In bonsai group plantings, you have the opportunity to use trees of varying ages (apparent ages) to introduce dynamism into your composition. Just as a composer or musician uses the softer, more quiet sections of a piece of music to enhance and contrast with the bolder or louder sections, young trees in a bonsai group planting provide interesting and dynamic contrast to older trees in the group.

Descending branch angles

One way of indicating advanced age with bonsai is to angle the branches downward. As trees age, the weight of their extending branches often causes them to droop downward. Furthermore, the cumulative effect of heavy snowfall causes many trees’ branches to grow downward from the trunk — more so as time passes. This characteristic is usually found on conifers, but sometimes with deciduous trees as well.

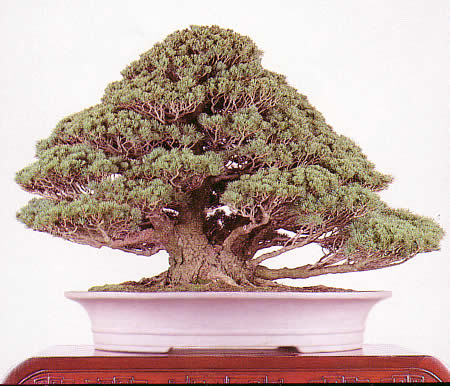

Well-developed surface root structure

When trees grow old, they usually show a more developed and more visible surface root structure than younger trees do. The apparent age of a bonsai is increased when this feature is well developed (as in the photo below).

Exaggerated trunk girth

In many cases, very old trees have large, even massive trunks as compared with their height. Like the issue of perspective described before, this feature can enhance the impression of age as well as size.

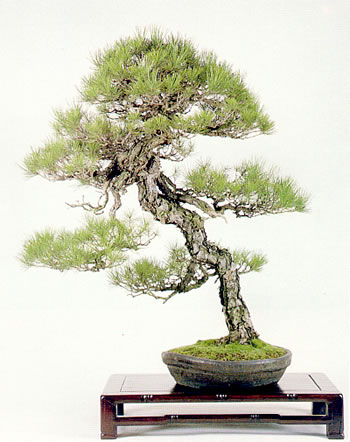

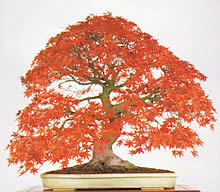

Open foliar structure

Full, lush canopies that cover the structure are typical of young trees or even mature trees, but seldom very old trees. When trees grow old, they tend to have more sparse foliage and a more open composition. Opening the foliar structure of your bonsai can work with other indicative features to add an air of age to the tree.

A more visible structure

As shown in the previous images, younger trees have more lush foliage, which tends to cover up the often-leggy branch structure. As trees age, their branch structure matures and shows more character. At the same time, the foliage becomes sparser and more of the structure becomes visible.

Since we tend to associate a more visible structure with older trees, styling your bonsai to show more of the branch structure can aid in conveying a sense of great age.

Signs of damage

As trees go through life, they are constantly enduring the harshness of nature; periodic damage from wind and cold, attacks from insects and disease, etc. Incorporating these features into your bonsai design can enhance the appearance of age.

Note that this kind of damage should not seem to be recent. In order to be convincing, scars should be bordered by the swell of healing tissue. Scars should not be round, but rather irregular in shape. Dead wood should be aged in appearance rather than look newly carved. A broken apex should appear to have been replaced some time ago.

Rough, consistent bark (species specific)

Trees start out in life with smooth bark and many of them form rough or corky bark as they age. Throughout their lives, they will have areas of old, developed bark and younger branches with smooth bark. Very old trees have a consistent bark texture over their entire structure, but for the smallest twigs.

It takes time to develop, but a bonsai with a consistent, rough bark will appear older than one without rough bark or with rough bark only on certain parts of the trunk or branching. There are ways of speeding up the bark development process, but the most effective tool is simply time.

Environment

Telling a story can be an important part of bonsai art. An important part of this story is usually concerned with the environment that a bonsai and companion elements suggest. Trees in nature have their environment surrounding them. Bonsai, however, are removed from their natural setting and are growing in pots. As bonsai artists, we have to use artistic means of suggesting the environment that is part of each bonsai’s story.

Display companions

There are various ways of suggesting a tree’s environment and most of them are represented by the basic components common to the traditional formal display of bonsai. A simple companion plant that comes from the environment you wish to indicate can be a good environmental clue. Likewise, a scroll that depicts a mountain range or a marsh plant or a storm or a single mountain far away can offer the necessary reference.

A stand is typically used for displaying bonsai and it serves a few functions. First of all, it is an element of formality. Artistic display is usually formal and the stand helps to convey this theme. Further, the stand is useful in conveying various levels of importance and/or geographic location within the display. This, too, is part of the formality of the display.

A companion plant, for instance, might have its own short stand, but the bonsai tree is the focus of the display, so it is on a higher stand. Conversely, a meadow species bonsai might occupy a short stand while the companion distant mountain suiseki would be on a taller stand, indicating the natural arrangement of these elements in nature.

There is much to this formal display aspect of bonsai art. It is a subject that is vital to artistic bonsai display and is beyond the scope of this text. I highly recommend that the reader become familiar with these principles through research in other texts, educational venues and lots of display composition practice.

Pots

Pot size and shape can be effective for indicating environment. Here are just a few of the ways for using these elements for this purpose.

Note: this section will not be concerned with the basics of matching pot to tree. The fundamentals of pot selection should be understood before one attempts to apply the artistic principles outlined here.

Indicating a tree growing in a rocky crevice

An unglazed pot that is taller than its width can help to suggest an exposed rocky cliff with the tree growing in a crevice. This is effective when used for a cascade tree with a thinner trunk

Another pot form for this kind of image is the crescent pot. Crescent pots usually have the texture of a rocky cliff and the way that the crescent tends to envelop the tree’s base helps to further enhance the image of it growing from a rocky crevice.

Yet another, more literal way to portray this environment is to plant the tree directly on a rock. This can be done either in the root-over-rock style or thesaikei style, with the tree planted in a crevice or in soil that is on the rock.

Indicating a tree growing in a wide meadow

the images of a wide meadow. To enhance this image, a flat lip on the pot rim can add a sense of expansiveness. This kind of image works best with trees that are commonly found in meadows and when shaped in broom or informal broom forms.

These bonsai seem to have been taken directly from expansive meadows. Both their peculiar growth form and the pots they grow in help to convey this idea. Photos courtesy of Bonsai Today

Indicating a windblown prairie or moor

Indicating a forest hill

Both a shallow oval pot and a convex slab are effective in indicating a hill for a forest planting of bonsai trees. In these cases, it is also helpful to mound the soil slightly to assist in portraying this image.

Moss

Mosses of various types are commonly used to dress up a bonsai for exhibit display. A thick carpet of lush moss covering the soil can offer the impression of a lawn of grass. While this alone can be appealing, there are ways to use moss to provide specific context to your bonsai composition.

Moss can add a sense of age and permanence to the composition. You may have repotted the tree only last week, but if you have applied moss to the soil correctly, you can make it seem like the tree had been growing in that spot for decades or centuries. Even so, this is most effective if the moss has had time to grow up slightly onto the surface roots or even the trunk. Note that this is not always so and this kind of moss growth is not always appropriate and sometimes even detrimental to the tree’s bark.

When mosses of different varieties are used, it can offer the impression of an alpine meadow or even a mossy pocket in the mountains. A patchwork of moss might be effective for indicating a harsh environment while a solid carpet indicates more of a serene environment.

If the moss has flower “flags,”, be sure that they all point in the same direction. Further, make sure that this direction is consistent with the flow of your bonsai’s growth. This little detail could complete or detract from the integrity of your composition.

These somewhat literal references to nature can be effective for communication in bonsai art. There are, however, some elements of nature that are not so useful in our efforts, as we will examine in the next chapter.